By C. Chung and E. Kinman, with assistance from E. Averbuch, J. Rose and C. Portis

When and where did the first cases of Ebola appear?

The history of Ebola is longer than some might think. The first known outbreaks took place in 1976 in areas that today are parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. These were independent outbreaks of two genetically distinct forms of the virus, Zaire ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus, which were introduced to the human population from two separate sources.

In the earliest outbreaks, healthcare workers and scientists did not understand the way the Ebola was transmitted. They often reused needles and did not wear protective gear. By the mid-1990s, it became standard to wear masks and gloves, and to use disposable needles. This dramatically reduced the rate of infections among healthcare workers. Today, almost 75% of infections are contracted from close family members sick with the virus.

The most recent major Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreaks took place in 2008-9 and 2014-16 in Central and West Africa. There were a few steady cases in between the two outbreaks, but many went unrecorded since they occurred in rural areas with undeveloped health care and transportation systems. In 2009, there was some confusion between those infected with Shigella, a bacteria with similar symptoms to Ebola, and those infected with EVD. It was later confirmed that 160 people died of Ebola virus in 2009. Later in 2009, a third outbreak occurred in which four people were confirmed to be infected although there were forty-two other suspected cases and two-hundred others being monitored. Ultimately, these cases prepared the DRC for the major outbreak in 2014-2016.

What major outbreaks have there been? When/where did these occur?

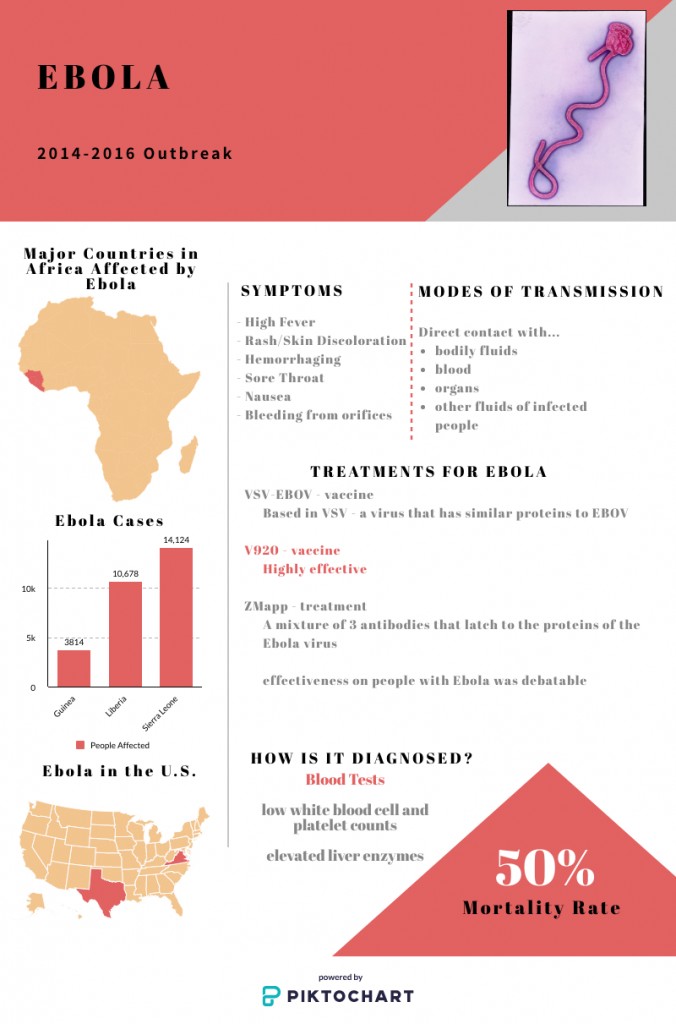

The most notable outbreak occurred in 2014-16 in Western Africa (it originated in Central Africa, in the DRC). During this time, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia were most affected by the virus. In total, there were 28,600 infections, 11,300 of which resulted in death. This constitutes a 50-70% mortality rate for this outbreak. Just like in the 2009 outbreak, in which Shigella was confused for Ebola, cases of Shigella were mistaken for Ebola throughout 2014-16. Due to a rising infection rate, on August 8, 2014, the director of the World Health Organization declared the outbreak an international public health emergency. In response to the international public health emergency, UN officials determined that 1 billion dollars would be needed in order to contain the outbreak in September. China, Cuba, the United States, and the United Kingdom provided aid to the UN to fight Ebola.

Source: WHO

What was the initial government response to the 2014-2016 outbreak?

Prior to the 2014-2016 outbreak, the Democratic Republic of Congo had experienced six outbreaks of Ebola, so they had knowledge of the disease and what was necessary to prevent an outbreak, plus the WHO was providing the country with aid. When Ebola resurfaced in August of 2014, the Minister of Health went to Boende, where the outbreak was discovered, in order to evaluate the current condition. He took two trips to the infected district throughout the first month of the outbreak, which motivated personnel and aided in public awareness. Health workers within that district were alerted as well as national authorities. Blood samples were transported to a lab for genetic testing and results were delivered within hours. Additionally, contact tracing began almost immediately and this aided in the containment of the virus.

Source: WHO

How did local factors shape the outbreak?

The majority of early outbreaks occur in in rural, underdeveloped areas. The lack of infrastructure prevented EVD from “coming into the city, so [people] die in their rural villages” (Oldstone 216). Throughout history, Ebola outbreaks have stemmed from rural villages, as in the 1970s, there was an outbreak with a 90% death rate in rural villages along the Ebola River and in 1995, an outbreak occurred in Kikwit, the DRC’s most “agriculturally productive area.” Though the outbreaks occurred in agricultural areas, the government blocked access between cities to prevent the spread, similar to the preventative measures taken against COVID-19 today. Additionally, within the rural communities at the origin of the outbreak, many infections went unreported in fear that “prospective tourists would cancel their visits” (Oldstone 216).

The 2014-16 outbreak spread to urban areas, which alarmed officials and healthcare workers, and facilitated a much more rapid spread of the disease. The disease appeared in the capitals of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. According the to CDC, this occurred because of “weak surveillance systems and poor public health infrastructure.”

Rebel groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo hindered the abilities of health care workers to provide treatment in various villages during the unrelated 2014 outbreak in that country. One of the most disruptive terrorist groups is ADF (Allied Democratic Forces), which is a Ugandan terrorist group that began in 2014 and is still around today, despite the UN capturing the leader of the organization in 2015. The UN documented that ADF staged two attacks on MONUSCO (United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) peacekeepers. In 2013 and 2014, MONUSCO patrols were attacked on a road between Mbau and Kamango and a MONUSCO vehicle was attacked with grenades not far from the Mavivi airport. These attacks resulted in 5 peacekeepers being injured.

Aside from the ADF, there are other rebel groups that pose threats to communities affected by EVD and the health care workers present. One of these is the Hutu Power Group which is in conflict with the DRC’s military. This conflict is termed as the Kivu conflict, which was heightened in 2015. Whole villages were attacked and sexual violence was used as a weapon of war. The Hutu Power Group was just one of the 100 other armed groups in the eastern part of the DRC.

The DRC has attempted to stop groups like the ADF and Hutu Power Group, but since their government is still developing they are not equipped with the appropriate resources to fight these violent groups.

The government of the DRC lacks stability and effectiveness because of their long history and civil wars over the natural resources in the DRC. This resulted in the DRC having the lowest per capita incomes in the world and second-rate transportation system which equally contributed to their weak economy.

What was the initial international response to the 2014-16 outbreak?

When the 2014-2016 outbreak emerged, the World Health Organization responded by implementing a three phase plan. The first phase (Aug.-Dec. 2014) revolved around containment and awareness of EVD. In this initial phase, the number of treatment centers and patient beds was increased and teams were trained and hired to deal with all implications of the virus (especially focused on proper burials, as Ebola could be transmitted after death). Phase two (Jan.-July 2015) involved increasing medical presence, supplies, and response to EVD. During this stage, case findings were increased, contact tracing began, and community engagement was encouraged. Contact tracing is the process of locating people who have come in contact with those who have been infected with the virus. This phase was especially successful, as it brought the Ebola outbreak under control and reduced death and case numbers to the single digits. Finally, Phase 3 (Aug. 2015-mid-2016) focused on isolating the disease by limiting outside contact and inadvertent consequences. This phase increased the process of finding those infected with EVD, contact tracing, and handling deaths. Additionally, community involvement was increased, aid was provided for Ebola survivors, and the human to human transmission of the virus ended. By early 2016, health facilities which were better equipped to assess Ebola virus patient statuses were established.

Not only was WHO involved, but also the United Nations. In 2014, the United Nations created UNMEER (UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response), an international program to contain the Ebola outbreak and the first emergency health mission by the UN.

Source: WHO

How did the US government respond to the outbreak?

In addition to providing financial aid to the United Nations in 2014, the CDC sent 133 medical specialists to the DRC and its neighboring countries. The CDC specialists were limited to areas surrounding the source of the outbreak and were not able to enter directly into the primary infected district, as there was armed conflict in that area, as well as other outbreaks of cholera, measles, and poliomyelitis, which had yet to be brought under control. In addition to deploying specialists, the United States provided technical guidance to the Democratic Republic of Congo’s government, as the US had experience with outbreak protocols. For example, CDC aided in the advancement of the ring vaccination protocol, updated vaccination training materials, trained and deployed hundreds of Field Epidemiology Training Program graduates, and finally, developed multiple EVD surveillance and vaccination tracking systems. This proved to be essential for the DRC, as their previous method of recording was manual.

Source: CDC

How was the outbreak handled in the media?

The threat of the outbreak was misrepresented by US news outlets. This is demonstrated in a public poll which indicated that 85% of respondents believed one would be able to contract EVD through sneezing or coughing. This statistic signifies that 15% of respondents were unaware that EVD can be transmitted through sneezing or coughing, as EVD is transmitted through the bodily fluids of those who are sick or even dead. Additionally, 48% believed that EVD could be transmitted through asymptomatic people. This means that almost half of the respondents believed false information, as Ebola can only be spread through those who are displaying symptoms. The misrepresentation of EVD was heightened by the fact that only 32% of new stories included scientific information about the disease such as the disease contagion pathways.

Source: CDC

EVD is transmitted through the bodily fluids of those who are sick or even dead.

How has media handling of Ebola changed over time?

In the first month of the COVID-19 outbreak, it has received more news coverage than the Ebola Virus in the past few years. When EVD first had it’s outbreak, there was plenty of news and media coverage on what it was and how to avoid it. COVID-19 is currently having that same press of data and statistics, and overall the negatives of this virus. It is possible that COVID-19 could possibly diminish in the press in just a few months or few years. As relevance of the 2014-2016 outbreak has diminished in the minds of Americans over time, news outlets in 2018 seldom covered current events surrounding the disease. Additionally, the US press was grossly accused of sensationalizing the threat of the EVD virus to the American public, yet, no one is accusing the press of sensationalizing the threat of COVID-19 and it has had more press than EVD statistically speaking, as seen in TIME Magazine.

Source: TIME

What issues of discrimination or stigmatization resulted from the outbreak?

A product of the many EVD outbreaks has been a stigma against pregnant women within heavily infected areas, many falsely believe that these women are more likely to die of EVD. This misconception can lead to less care which is contrary to what they need. Pregnant women that have been exposed to or have contracted EVD need attentive care from both obstetricians and EVD-trained medical professionals, because EVD can raise the probability for miscarriages and early labor. Also, if the mother has EVD then the virus can be passed to the child and others through breastmilk and other bodily fluids. To combat these stigmas and promote care for pregnant women with EVD the World Health Organization released a standard care guideline for breastfeeding and pregnant women.

Source: WHO

What is the status of the disease now? What is the infection rate?

On February 12, 2020, the WHO held a teleconference to discuss the status of the Ebola virus. The meeting included the International Health Regulations Committee (IHR) and the UN Emergency Response Coordinator; they focused on security and preparation for future outbreaks. The WHO still considers EVD to be a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), as the risk is high locally and regionally, but low globally. However, other diseases are taking precedence such as COVID-19, measles, and cholera.

In the DRC as of February 10, 2020, there were 3,431 EVD cases, 3,308 confirmed cases, 123 suspected cases, 2,253 deaths, resulting in a 66% death rate.

Although there is less international concern for EVD, there remain challenges to overcome in order to prevent another outbreak. These obstacles include: increasing community involvement in relation to precautions, securing health of medical workers, sterilizing medical facilities, improving treatments, and aiding in the recovery of EVD survivors.

One of the biggest challenges remaining to health workers is safety.

One of the biggest challenges remaining to health workers is safety, as more than 100 armed groups such as the Hutu Power Group function within the eastern part of the DRC, terrorizing villages and recruiting children for labor and child armies. These groups are a result of a developing and corrupted government and are partially fueled by the DRC’s mineral resources estimated to be worth $24 trillion. The mineral trade allows violent groups to function financially, but in 2010, the US passed a law preventing the buying of conflict minerals in order to drain the funds of armed militias. This law resulted in companies ceasing to purchase minerals from the DRC, which left miners without jobs and drove many of them to join rebel groups like M23 (March 23 Movement), which was supported by the Rwandan government during the Rwandan Genocide.

Source: WHO

What is being done to prepare for future outbreaks?

The World Health Organization has addressed the issue of preparedness regarding EVD and has created a plan for eradication that has been implemented in 9 countries of concern. Those involved in this plan have investigated 2,400+ potential and real EVD cases and have vaccinated 14,600+ medical professionals.

Source: WHO

What advances have been made?

Since the first occurrence of EVD scientists have developed vaccines, increased community involvement, improved communication, made a plan to prevent EVD, increased security, and created an EVD survivors program. The first vaccine for EVD was ZMapp which was the combination of certain antibodies to combat strains EVD. It was introduced in one of the outbreaks in the early 2000s but proved mostly ineffective. The more recent vaccine is V920, which was somewhat more effective and is currently the best available vaccine. Throughout the different EVD outbreaks, medical professionals and organizations such as WHO have worked with communities affected by EVD to implement appropriate security measures. As time has passed these measures and precautions have become more effective and more well received. The plan for working to minimize EVD outbreaks in at risk areas has been put to work in 9 countries. Along with this plan, further security has been put in place to monitor potential and confirmed cases of EVD.

Information about safe burial practices has also been provided to affected and at-risk communities. In West Africa, belief in the afterlife is strong. This means that people think it is important to bury their loved ones properly. This often involves cleansing and washing the body. If the deceased was infected with Ebola, such handling can easily transmit the disease.