By: Caleigh Dennis

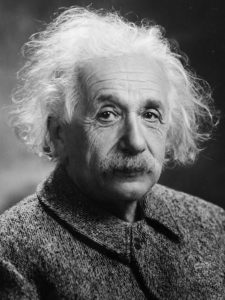

An undeniably prominent influence during the 20th century, Albert Einstein is best known for his contributions as a scientist, namely the theory of relativity. Although his scientific impact was immense and continues to impact physics today, to truly understand Einstein in his entirety, one must examine all aspects of his life and, most importantly, the inter-connectivity between these facets. A Jewish man living in Germany during the 1920s, Einstein experienced intense ethnic and religious discrimination, and as Judaism was an important identifier for Einstein, it permeated all aspects of his life. To understand Einstein as a scientist, is to understand what it was like to live as a Jewish man during his time period, a time filled with anti-semitism, nationalism, and resentment.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity was first published in 1915, following his paper on special relativity, and described a geometric theory of gravitation while providing slightly differing predictions from those of classical physics. In his paper, Einstein described gravity as a property of space-time, more specifically the curvature of space-time, where massive objects affect its shape. These curves in space-time then affect the paths of objects; this physical process is known as gravitational force in classical physics. The general theory of relativity shows how even the path of light can be bent as it enters a gravitational field, a phenomenon Einstein explains: “A curvature of rays of light can only take place when the velocity of propagation of light varies with position.” This phenomenon cannot be explained using the special theory of relativity, as a consequence “We can only conclude that the special theory of relativity cannot claim an unlimited domain of validity,” and these shortcomings are compensated for by the general theory of relativity, which handles light in an accelerating reference frame.1

Einstein’s theory of relativity was seen by many as an important breakthrough in science and physics, but many scientists still opposed the theory, largely for unscientific reasons and, according to Einstein, reasons principally grounded in his identity as a Jewish man. In a letter titled “My Response. On the Anti-Relativity Company,” Einstein aired his grievances writing, “Under the pretentious name ‘Arbeitsgemeinschaft deutscher Naturforscher’ a variegated society has assembled whose provisional purpose of existence seems to be to degrade, in the eyes of non-scientists, the theory of relativity as well as me as its originator.” He later goes on to mention, almost as an aside, that, “if [he] were a German nationalist with or without a swastika instead of a Jew with liberal international views then…” Trailing off into an incomplete sentence, Einstein continues on to use unbiased reason in order to debunk the claims of the society. Although Einstein had more than proven his capability as a scientist, the outside world remained unable to separate his work as a scientist from their own anti-Semitic and discriminatory beliefs. This fact was blatantly obvious to Einstein and fueled his political belief in Zionism, a movement for the establishment of a Jewish state.2

Although Einstein is best known for his contributions as a scientist, he was also highly concerned with the politics of his time, as both an outspoken Zionist and a globalist. In an interview titled “How I Became a Zionist,” Einstein states, “Until one generation ago, Jews in Germany did not consider themselves as members of the Jewish people…They have attended mixed schools and have adapted to the German people and to their cultural life. Yet, in spite of the official equal rights they enjoy, there is a strong social Antisemitism.” Einstein understood that although the Jewish population in Germany had ostensibly assimilated into the German culture, they were still treated as second class citizens. It was largely because of this Antisemitism which Einstein had experienced first-hand in his work that he believed in the establishment of a Jewish state.3

Einstein established himself as one of the most prominent figures of the twentieth century and created a legacy that has continued to exist long after his death. Despite this fact, in many ways his career as a scientist overshadowed the many other important factors that made up the man he was, from his cultural identity to his political beliefs. Due to the interconnected nature of human existence, it is important to understand Einstein holistically, as both a man and a scientist.

Work Cited

1 On the Special and General Theory of Relativity (A Popular Account): https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/340

2My Response. On the Anti-Relativity Company: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol7-trans/213

3How I Became a Zionist: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol7-trans/250

____________________________________________________________________

Demystifying Einstein: The Human behind the Brain

By: Mohini Misra

Albert Einstein: a man of renowned intelligence and groundbreaking ideas. Today, thinking of him elicits awe as we try to comprehend the raw power of intellect that propelled him. From pioneering ideas of relativity to refining the known physics of his time, Einstein defined central pillars to modern physics. It is easy to know him abstractly; we are, indeed, more familiar with his ideas rather than his character. However, Albert Einstein’s more human side permeates into his writings and discussion, making him a multidimensional, real figure.

In his primary paper on special relativity, On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies1, Albert Einstein analyzes differential equations, makes conjectures about the nature of mass and light, and probes the truth of our world– all to come to the conclusion that the speed of light is constant regardless of frame-of-reference. Undoubtedly, this is an advanced topic that remains difficult to comprehend. However, Einstein builds up his ideas gradually so that they are understandable. He starts by not only drawing on, but also explaining, previous physics principles such as Maxwell’s electrodynamics theories. He then re-defines frames of references, inviting the reader to “consider a coordinate system in which the Newtonian mechanical equations are valid” and then only expanding upon that simple statement. He includes examples of moving rods and clocks, relatable objects to define matter and time, thus making his paper understandable even to the layman. Although he was a genius in his ideas, Einstein could convey them to the typical educated person, showing that he was simultaneously a scientist and an everyday human.

The same humanity shows through in scientific discussions. In such discussions, Einstein and several scientists debated and reflected on a paper, theory, or presentation. Often, their conversation was transcribed, so we now have a record of his interactions in the scientific world. In these, he spoke not only with conviction and confidence, but also with humility. One of the most refreshing lines in these discussions is in Discussion of Szarvassi2, when Einstein admits “I cannot comment on that, because I did not enter sufficiently into the spirit of this consideration.” As a man that is known for being right, Einstien could acknowledge his flaws and submit to those who were more knowledgeable than him on certain topics. In discussions within the scientific community, he was often right, sometimes wrong, and more human for the ability to be both.

Perhaps the most powerful way to understand the concrete person that Einstein was is to read his personal correspondence. The letters he writes to family and friends discuss typical topics, from milestones to the intensifying political climate to everyday life. On June 28th, 1902, he wrote to his wife Mileva3, “You can’t imagine how tenderly I think of you when we’re not together” and “life’s full of good cheer and tender feelings”. These phrases convey the sweet love of an ordinary man who misses his wife. Even when writing letters to his friends, he exhibits common relatability. To Michele Besso, a close friend and co-worker, he wrote about topics such as married life and his sister, and jests at those he finds amusing. Of course, he does discuss some scientific principles in his letters, but they are integrated casually. In a letter written January 22, 19034, he concludes by writing “Pardon my bad handwriting. I wrote in bed.” This simple phrase paints a sharp image of Einstein living as we all do, facing trivial problems as we all do, and interacting with others as we all do. In speaking with those he loved, Einstein is no different than we all are.

Through his writings, we are able to view Einstein as an actual person, rather than a mere symbol of intelligence. Though he had remarkable brain power, he was still subject to emotions and the vicissitudes of life. In this way, he is a powerful example that scientists are not solely “nerds” or “lab personnel” but also are able to live as normal people– even if they redefine the study of physics while at it.

Works Cited:

1On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol2-trans/154

2 Discussion of Szarvassi: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol2-trans/392

3 Letter to Mileva (June 28, 1902): https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol5-trans/26

4Letter to Besso (January 22, 1903): https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol5-trans/29

___________________________________________________________________________

The Progression of Einstein’s Scientific Papers Throughout his Career

By: Kathryn Jenkins

In Einstein’s first paper, written in 1895, he explores the movement of ether caused by an electric current and how it forms a magnetic field. Due to his lack of materials, he explores what experiments could be done on the topic, as well as what findings could be discovered through research. In regards to the movement of ether, he asserts that the change in velocity of an ether wave is directly proportional to the change in elastic force. This is a direct contrast to Einstein’s arguments in future works, most notably his theory of special relativity. In this theory, Einstein argues that light travels at the same speed c in any inertial frame. He neglected ether altogether, saying the laws of physics apply no matter how one is moving. This is based off of his two postulates: that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial reference frames, and that the speed of light in a vacuum is measured to be the same in all inertial reference frames. Both postulates parallel his final theory. The first postulate was not a new idea, however it had not been applied to Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism. The second postulate had been supported by a recent experiment, however it was a counterintuitive idea at the time. It took more materials, as well as an ability to perform experiments for Einstein to make this discovery, ultimately moving on from his initial paper’s arguments.1

In a later paper written by Einstein, published in 1924, Einstein discusses field theory, and the possibility of it being the key to solving the unknowns about quantum. According to existing theories at the time, the initial state of a system could be freely chosen, with the differential equations then delivering the temporal continuation. However, according to newer knowledge about quantum states, this feature of the theory did not entirely correspond to reality.2

While in both papers Einstein explains and explores his scientific research, there are stark differences noticeable throughout both. Most prominently, readers can discern his drastic change in language throughout his writing, becoming much more advanced and thought out in later works. In his first paper, he uses terms such as “basically”, interesting”, and “probably”, not terms one typically hears in scientific writing. This can most likely be accredited to his lack of experience and scrutiny during his first work, being much more casual than his works later in his life. I, however, enjoyed reading this scientific paper, as it made Einstein seem more relatable. It is always easy to forget that even the greatest scientists come from humble beginnings. And, while I am no Einstein, it is fascinating to see that his writing at that time appears to be similar to my own.1

Readers can also observe that as Einstein gained more experience and opportunities, his confidence in his writing also improved. While introducing his first paper, Einstein states, “May the indulgence of the sympathetic reader match the humble feelings with while I present these lines”.1 He hopes that his uncle, to whom he is sending this paper, will not be too harsh in critiquing his work. Similarly, this can be supported by looking at a letter written by Einstein to his uncle. Einstein writes, “I hesitated to send you this writing, because it deals with a very special topic; besides, it is rather naïve and imperfect, as might be expected from such a young fellow like myself”.3 Despite becoming one of the most renowned scientists in history, Einstein again becomes relatable to the reader, being timid in showing his work to others. This is a stark contrast to his work in later years as he gained notability and veneration. Einstein holds a lack of confidence in his first work that truly displays what courage and self-assurance he gained after acquiring more experience.

Einstein’s first and last papers hold stark differences—and not just in their subjects. Einstein’s language and confidence dramatically changed throughout the years, becoming more advanced over time. In later years, he went into more complex detail with his descriptions and gained more self-confidence in his work. Despite the contrasts, one thing remains constant: Einstein always strived to do groundbreaking research and dedicate himself to his craft. He shows that everyone comes from humble beginnings—and if he can do it, maybe you can too.

Works Cited:

1On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol1-trans/26

2“Does Field Theory Offer Possibilities for the Solution of the Quantum Problem?”: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol14-doc/369

3To Caesar Koch: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol1-trans/28

_______________________________________________________________

Albert Einstein Prevented Scientific Collapse in WW1

By: Megan Robertson

Being “the most influential person of the century,” according to The Times, means that they have impacted the world more than any other person in their era. In the 1900s, World War One and World War Two had occurred, which spawned a great increase in these people. But, the most influential of them all was Albert Einstein. Through his persistent writings, whether it be academic or political, he brought the scientific community together in a time of great strain on internationalist ideas.

Albert Einstein was a pacifist. He believed there was no need for violence. That being said, Albert Einstein was extremely opposed to WW1 because of it going against his pacifist nature and it interfering in the scientific community [4]. On September 29, 1920, Einstein sent a paper titled “Thoughts on Reconciliation” to New York that explained his worries of the scientific community becoming too involved in nationalism, rather than scientific internationalism. He states, rather explicitly, “The most valuable contribution to a reconciliation of the nations and a permanent fraternity of mankind is in my opinion contained in their scientific and artistic creations because they raise the human mind above personal and national aims of a selfish character” (Einstein). What Einstein means by this is that he believes that in order to remain an intelligent nation after the war they must continue to share scientific discoveries and not be so nationalist that one would refrain from sharing important breakthroughs. The importance of this is that not only did he urge others to maintain internationalist ideas (ideas that were widely considered to be dangerous during WW1), but he matched his words to his actions. He himself was reaching out to other nations sharing his ideas in hope that it would bring about a new sense of trust between nations.

Although his political opinions were far less widely shared across nations, he was “the most influential man of the century” for a reason. Through is scientific findings he was able to reach and influence almost every nation on the globe. Even today his findings are still being analyzed and we are discovering the depth in which they are applied to other breakthroughs. For example, he held a lecture explaining his general theory of relativity (his most popular lecture of the time), and he was forced to create another date to hold the same lecture because the lecture hall was filled to the brim even with students outside unable to listen in [1]. This is just one example of the reach of his papers. One can only imagine what his influence would be if he wrote a scientific paper on the breakthrough that changed practically all of the physics…. Oh, wait!

Imagine no more! Einstein’s paper that introduced his Generalized Theory of Relativity changed the world [3]. His theory explained that 1) the speed of light remains constant no matter the frame of reference that one is in (whether one is accelerating or not) and 2) space and time were woven together to form what is known as “space-time.” In simpler terms, Einstein discovered that gravity is not what Isaac Newton believed to be true. His most famous explanation his one that involves an elevator suspended in space with no interferences acting on it (field or force). He explains that an “artificial gravity” can be created by accelerating the elevator in space. This acceleration would push a person to one side of the elevator making one feel as if they were being affected by a gravitational force when, in fact, there is none present. Another famous explanation of this theory revolves around a bowling ball and a trampoline. He explains that if a bowling ball (represents a large mass like a planet) was set on a trampoline (represents space-time), then there would be a distortion around the bowling ball which would represent what we perceive to be the effects to gravity. However, this “distortion” does not connect to Isaac Newton’s Theory of Gravity because his theory implied that gravity was an acceleration that originated from the center of a massive body, when in reality, according to Einstein, the effects of gravity originate from the distortion of space-time. The importance of this discovery is incomprehensible.

With this new information, physicists had to rethink everything they thought to be true. They came to the conclusion that their previous notion of physics would have to change in order to conform to Einstein’s theory. I repeat. All of physics had to change to conform to Einstein’s theory of relativity. Not only this. His papers are world renown in general, but his most notable paper (yes even more notable that the theory that changed all of physics) explains the connection between energy and mass [5]. I would find it hard to believe that you have not heard of the equation E=mc^2. Einstein explained very small amounts of mass have a large amount of energy and vise versa. These discoveries were groundbreaking in their time, and Einstein shared this information with everybody who would listen to him. His willingness to cross national borders with information allowed for others to follow in his footsteps. Although the information shared from others would not be as significant, it did allow for the idea that intellectuals did not have to cut communication when their respective nations split ties.

In mid-October of 1914, Einstein pleaded to the Europeans to maintain intellectual discourse internationally [2]. He did this by stating the reasons in which we as people of the world need internationalism and why people of their individual nations need internationalism as well. He states, “It would not only be a disaster for civilization but–and we are firmly convinced of this–a disaster for the national survival of individual states–the very cause for which, ultimately, all this barbarity has been unleashed.” The “it” that he is referring to in the manifesto of sorts is the discontinuation of scientific sharing. The First World War had just begun, and, frankly, I believe that Einstein was afraid that all he had worked for would be lost in the war. He witnessed the withholding of information in Germany due to lack of trust and nationalist pride, so he wrote a “Manifesto to the Europeans” that explained that if they continued along the path in which they were headed, then they would face the end of the scientific era. However, this did not occur because of the influential people like Einstein who shared ideas for the well-being of the world rather than withholding information for the benefit of one specific nation.

Overall, Einstein was the most influential scientist of the 1900s, and he saved the world from guaranteed scientific collapse by writing world renown documents that bridged nations in conflict and by providing an example in which others should follow in regard for sharing information. Einstein’s contribution to society was received politically and scientifically, which means that Einstein was not only the most influential scientist of the century but also the most influential politician of the century by this logic. That being said, Einstein saving the world from scientific collapse is just one of his many contributions to society.

Works Cited:

[1] Einstein, Albert. “Volume 7: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1918-1921 (English Translation Supplement) Page 201.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol7-trans/217.

[2] Einstein, Albert. “Volume 6: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) Page 28.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/40.

[3] Einstein, Albert. “Volume 6: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) Page 3.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/15.

[4] Einstein, Albert. “Volume 6: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) Page 96.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/108.

[5] Einstein, Albert. “Volume 6: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) Page 96.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol6-trans/108.